Transnational Repression by the Russian Federation: Threats, Tendencies, Solutions

Joint Research

Interim Report, 2025

Research & Authors

Consortium: Collective Action Brussels Think Tank (CABT), OVD-Info, Vyvozhuk, Cedar

Desktop Analysis of TNR Cases: OVD-Info http://ovd.info

Online Questionnaire: Vyvozhuk http://zhuk.world

Interviews: Collective Action Brussels Think Tank (CABT) http://cabt.team

Editor and Cover Design: Collective Action Brussels Think Tank (CABT) http://cabt.team

EU Outreach: Collective Action Brussels Think Tank (CABT) http://cabt.team

Graphical Design: Cedar http://cedarus.io

We extend our gratitude to the projects and partners who contributed to the production of this report, including Freedom House, Kovcheg, the Consuls of the Anti-War Committee, and other local partners.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are permitted, provided that the source is cited.

© Research Center «Collective Action Brussels Think Tank» (CABT)

May 2025

Executive Summary

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia’s use of transnational repression (TNR) has expanded dramatically in scale and reach. A mass exodus from Russia — approximately 900,000 people, representing the largest political migration since the 20th century — has triggered new security and legal challenges. Initially seeking refuge in the South Caucasus and Central Asia, many dissidents have since relocated to the European Union, bringing the risks of repression into the EU itself.

While acts of violence still occur, Russia’s methods have become increasingly covert, administrative, and digital. This shift creates new challenges for EU member states, whose sovereignty, legal systems, and democratic frameworks are being tested by authoritarian interference.

Assessment. Between 2022 and 2024, the average annual number of TNR cases increased by four to eight times across fifteen destination countries, including Armenia, Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, France, Georgia, Germany, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Poland, Romania, Serbia, and Spain (Annex 5). The increase has been particularly sharp in Russia’s near abroad, including Georgia, Armenia, and Kazakhstan, which have become the primary locations for Russian-led TNR activities. Notably, within the EU, Poland has emerged as one of the most affected member states. While case volumes inside the EU remain moderate, the trend is clear. Incidents have been also recorded in Italy, Spain, and Romania — all new additions to the list of affected countries. This expansion highlights the EU’s growing exposure to foreign authoritarian repression.

Russian tactics have shifted accordingly. Denial of Entry prevents access to safe territories, while Denial of Services blocks access to essential rights such as banking, placing exiles in precarious legal and economic positions. These measures erode protections for political refugees. At the same time, digital repression — including spyware, covert surveillance, and abuse of legal frameworks like Interpol — directly challenges EU sovereignty and undermines trust in European legal standards.

In parallel, state collaboration in certain regions has intensified. Central Asian countries, especially Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, have demonstrated significant cooperation with Russian security agencies, often facilitating unlawful detentions and forced returns of exiles. These actions not only endanger individuals in transit but also create unsafe corridors that push dissidents further toward EU territory.

Despite steps to address foreign interference, transnational repression remains insufficiently integrated into the EU’s security and human rights policies. Divergent national approaches, inconsistent legal recognition of TNR methods, and limited protection mechanisms have created exploitable gaps, exposing individuals and institutions to persistent risks.

Policy Implications. Addressing transnational repression is essential to defending both human rights and EU sovereignty. Russia’s use of legal, bureaucratic, and digital mechanisms to target dissidents within the Union constitutes foreign interference and undermines core democratic principles.

The EU should adopt a harmonized legal and policy framework to define TNR and recognize new tactics, including Denial of Entry and Denial of Services, as legitimate grounds for international protection. Asylum and residency procedures should be adapted to prevent politicized deportations and extraditions.

A dedicated EU-wide mechanism for monitoring TNR cases should be established, as current data relies solely on civil society and nonprofit efforts and remains fragmented. Systematic collection is critical to understanding the scale of the threat and developing responses.

In parallel, partnerships with civil society and nonprofit organizations should be deepened to enhance early warning systems and victim support. Finally, the EU must strengthen safeguards to prevent abuses of legal and digital infrastructure, including improved oversight of intelligence-sharing agreements and data privacy protections.

Conclusion. Russia’s campaign of transnational repression has become a European challenge. As it spreads westward and adopts more covert tactics, it threatens both individuals and the sovereignty of EU states. A coordinated and robust policy response is urgently required to protect European democratic values, sovereignty and maintain the Union’s role as a place of refuge for those fleeing authoritarian persecution.

Failing to anticipate and address the growing threat of transnational repression leaves EU member states exposed to a particularly insidious form of authoritarian interference — one that strikes at the very core of legal sovereignty and political freedom. As Anstis, Al-Jizawi, and Deibert (2023) note, this phenomenon reflects a fundamental clash between competing conceptions of sovereignty. In democratic systems, sovereignty is closely tied to the obligation to protect rights and uphold the rule of law within national borders. By contrast, authoritarian regimes increasingly view sovereignty as the prerogative to exercise control over citizens regardless of where they reside. This extraterritorial logic, often justified in the name of regime security, legitimizes practices such as cross-border surveillance, legal manipulation, and forced returns — actions that directly undermine the legal order and security of host countries, including EU member states. The Council of Europe has underscored the seriousness of such threats, emphasizing that they directly attack the rule of law.

Therefore, transnational repression must be recognized not only as a human rights violation, but also as a strategic effort by authoritarian regimes to impose their sovereignty beyond their borders. While the issue has gained increased attention — including through a recent PACE report and the appointment of a dedicated rapporteur — a significant gap persists between recognition and implementation. Without targeted and coordinated policies, victims will remain vulnerable, and the EU’s core democratic principles and institutions will continue to be tested.

Context and Strategic Relevance for the EU

Russia has long been a global leader in transnational repression (TNR), using harassment, legal manipulation, and violence to silence dissent abroad. Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, these practices have intensified and diversified, posing a growing security challenge for Europe. The war triggered the largest political exodus from Russia since the 20th century, with approximately 900,000 individuals fleeing the country. Many were anti-war activists, journalists, and civil society leaders, now facing risks of persecution beyond Russia’s borders.

Initially seeking refuge in the South Caucasus and Central Asia, dissidents have increasingly turned to the European Union. This shift has been driven by rising collaboration between Russian security agencies and local authorities in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, and Georgia, turning these regions into unsafe transit zones. As a result, Europe has become not only a destination but also a new frontline in the global contest between authoritarian and democratic notions of sovereignty.

While the overall volume of TNR cases within the EU remains moderate, the pattern is unmistakable. Documented incidents have emerged in Poland, Italy, Spain, Romania, and France, signaling a growing geographic spread. Poland has become one of the most affected EU countries, reflecting its status as a major hub for Russian exiles (see Footnote 1).

The tactics used have evolved significantly. Beyond traditional methods such as arrests and extradition requests, Russia now relies on Denial of Entry and Denial of Services, blocking access to safe havens and essential services. At the same time, digital transnational repression has intensified. Investigations reveal the use of spyware to monitor exiles and journalists in the EU, while Russian networks engage in covert surveillance and harassment operations. Notably, attempts to kidnap dissidents, such as the plot against journalist Roman Dobrokhotov in Berlin, illustrate the tangible threat within European borders.

Russia has also exploited international legal mechanisms to legitimize its repression. The abuse of Interpol’s Red Notices to target activists, journalists, and opposition figures within the EU circumvents legal protections and violates European human rights standards, as condemned by the Council of Europe.

These TNR activities threaten not only individuals but also EU sovereignty, the rule of law, and fundamental democratic values. Transnational repression undermines national jurisdictions, distorts asylum and residency procedures, and normalizes authoritarian practices within the EU.

Addressing this challenge is therefore not only a human rights obligation — it is a strategic security necessity. Failure to act leaves EU member states vulnerable to authoritarian interference that targets both the Union’s democratic institutions and the vulnerable individuals who turn to Europe for protection.

Finding 1: Transnational Repression by Russia Has Sharply Intensified Since 2022

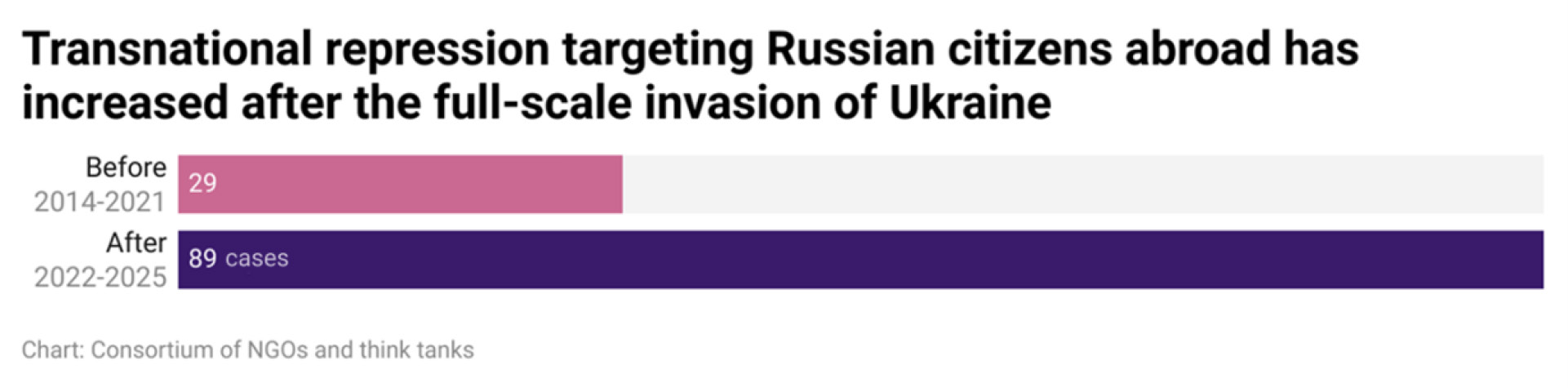

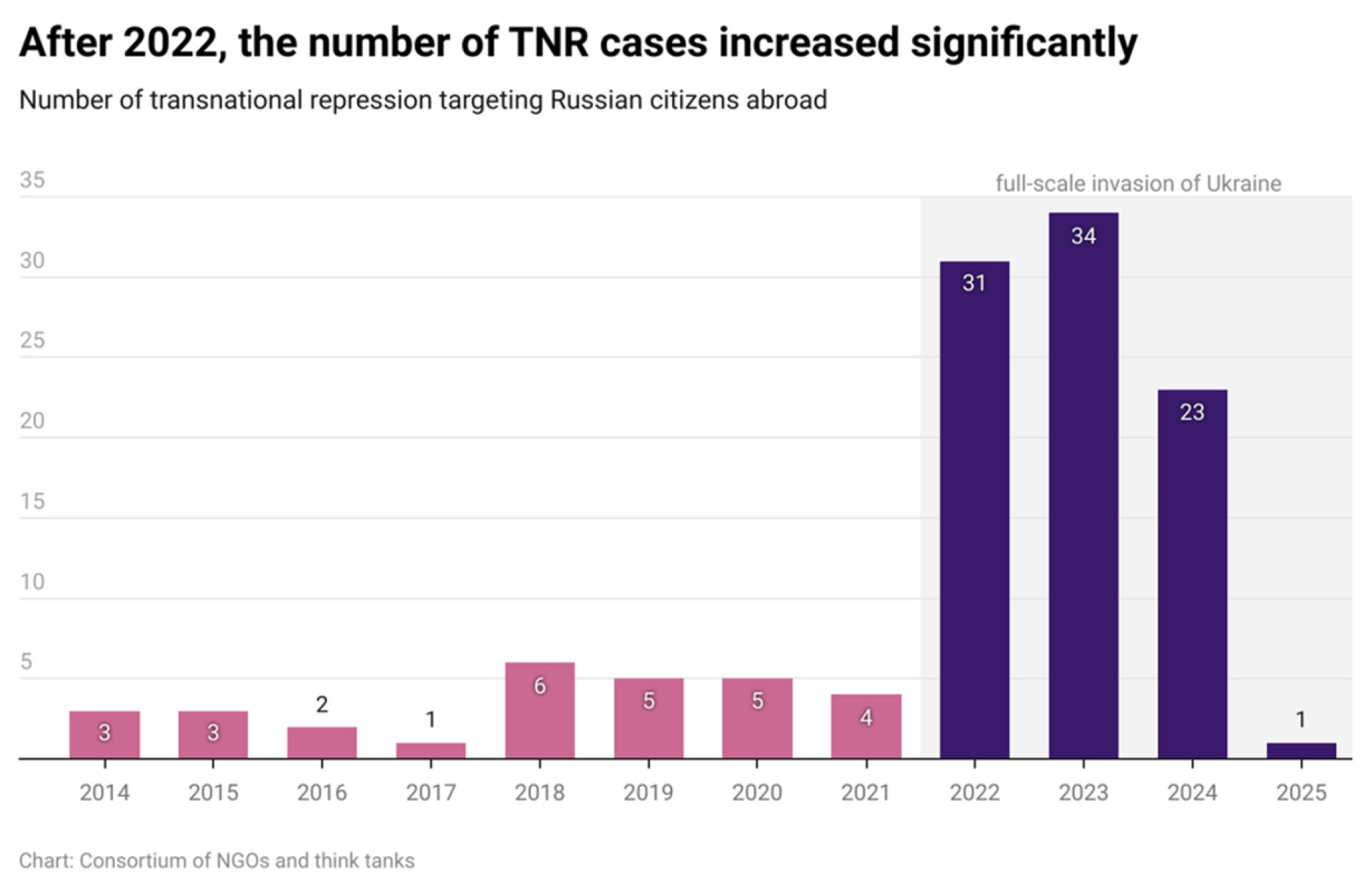

Since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s use of transnational repression has accelerated significantly. A comparison between the pre-war period (2014–2021) and the post-invasion era (2022–2024) shows a eightfold increase in the average annual number of documented TNR incidents (fourfold if Denial of Entry cases are excluded). In absolute terms, the number of cases has tripled when comparing the two periods—29 cases over eight years versus 89 cases over three years. While much of this surge has occurred in Russia’s near abroad, notably Central Asia and the South Caucasus, the effects are now felt within Europe.

The increase is closely linked to two major developments. First, mass emigration following Russia’s intensified domestic repression has driven many dissidents abroad, where they continue to be viewed by Moscow as threats. Second, Russia has adopted new forms of transnational repression, particularly Denial of Entry, which blocks individuals from entering or transiting through neighboring countries. This tactic has become widespread since 2022, contributing to the rapid rise in cases.

At the same time, Russia’s domestic crackdown has intensified, creating a direct and predictable driver for transnational repression. Data from OVD-Info shows that political persecution cases in Russia rose sharply from 521 in 2021 to 846 in 2022, remaining high in subsequent years. This rise forced many dissidents into exile, yet these individuals continue to be viewed by the Russian state as threats. As Dukalskis and colleagues have argued, authoritarian regimes treat growing exile communities as extensions of domestic opposition. This logic makes transnational repression a natural continuation of internal crackdowns: as domestic persecution rises, exiled dissidents become primary targets abroad. Russia’s expanded use of TNR since 2022 reflects this dynamic clearly.

While the escalation within the European Union has been more moderate, the threat is growing. Poland has emerged as one of the most affected EU member states (see Footnote 1), recording at least five cases of Russian-led TNR between 2022 and 2025. Other EU states have also begun to appear on the map of repression, reflecting the westward shift of this phenomenon.

Implications for the EU. The growing number of cases — and their increasingly diverse geographic spread — show that transnational repression is becoming a European issue. Without a coordinated EU response, targeted individuals risk falling victim to politicized legal procedures, denial of refuge, and indirect harassment. There is an urgent need for an EU-level mechanism to monitor and classify TNR cases, strengthen protection standards, and adopt a shared legal definition that reflects the evolving tactics used by authoritarian regimes.

Finding 2: Russia’s Shift to Covert Repression Methods Creates New Challenges for the EU

Since 2022, Russian authorities have significantly expanded and adapted their methods of transnational repression. While arrests, detentions, and extraditions remain in use, traditional violence has been increasingly replaced by more covert and legally ambiguous tactics. This evolution makes repression less visible, harder to document, and more difficult to address through existing legal frameworks.

Two methods have become central to Russia’s extraterritorial strategy. Denial of Entry has emerged as a prominent tool, with at least 43 documented cases since 2022. This tactic prevents activists, politicians, and human rights defenders from crossing borders and seeking refuge. Georgia has been a primary enabler, systematically refusing entry to Russian dissidents and thereby isolating them in vulnerable transit zones.

Equally concerning is Denial of Services, a quieter but destabilizing practice that has left many Russian exiles without access to essential services. These restrictions, including denial of access to financial and administrative services, force individuals to rely on temporary documents, increasing their vulnerability during travel and complicating their ability to secure and maintain residency in host countries.

As one Russian exile explains, this vulnerability creates constant uncertainty and danger:

«I am wanted and cannot travel to certain countries, such as Armenia and Kazakhstan, because they could detain me and deport me to Russia. We know for certain that the European Union and the United States will not expel to Russia, but in other countries, it’s a risk. I also know of a situation involving a friend who had a grey passport. He was flying to Georgia when a medical emergency occurred on the plane, and they considered landing in Turkey. However, with a grey passport, landing in Turkey is not possible because you can be immediately denied entry or even deported due to restrictions. This makes travel unpredictable and risky.»

— Ekaterina Alexandrova, former Navalny HQ staff member

These evolving practices are not isolated. They reflect a deliberate shift towards a repression strategy without borders — one that is difficult to detect, easy to deny, and challenging to counter legally. Critically, these tactics have already reached the European Union. While politically motivated violence has not disappeared — as illustrated by the fatal incident in Spain in 2024 — the increasing refusal of passport renewals for Russian citizens in EU countries has become a significant concern. This aspect of Denial of Services not only endangers individuals but also undermines national administrative systems, which are forced to handle politically charged and legally complex cases.

Implications for the EU. The emergence and growing use of Denial of Entry and Denial of Services within the EU require policy attention. These tactics expose gaps in asylum and residency procedures, blur the line between administrative decisions and political persecution, and risk making EU legal systems instruments of authoritarian repression. To address this, the EU should recognize these forms of TNR as grounds for international protection. Guidelines should be developed for asylum and residency processes, including a standardized approach to individuals denied passports for political reasons (e.g., holders of so-called ‘grey passports’).

Finding 3: Transnational Repression Is Expanding Geographically, with New EU States Becoming Affected

Since 2022, Russian transnational repression has expanded beyond its traditional hotspots in Central Asia and the South Caucasus. While states such as Kazakhstan, Armenia, and Georgia continue to cooperate with Russian authorities and remain central to TNR operations, repression is now spreading westward, increasingly affecting the European Union.

Georgia has become a particularly troubling example. In 2022 alone, at least 23 cases of Denial of Entry were documented. Though less visible than arrests or extraditions, this tactic systematically denies refuge to dissidents and isolates them in vulnerable transit zones. The scale and consistency of these actions raise serious concerns about Georgia’s reliability as a safe country for exiles and its growing exposure to Russian political influence.

At the same time, new geographic hotspots have emerged inside the EU itself. Since 2022, cases of Russian-led transnational repression have been recorded for the first time in Italy, Romania, and Spain — states that previously had no such incidents. This shift reflects a broader change in migration patterns, as Russian exiles increasingly turn to EU countries that are perceived as safer. However, the appearance of repression cases in these countries also highlights the gradual westward spread of TNR and the growing vulnerability of EU states to authoritarian interference.

Implications for the EU. The expanding geography of transnational repression demands policy attention. As new EU member states become affected, there is a risk that TNR tactics will become normalized and more difficult to detect. To prevent this, EU institutions and member states should strengthen structured cooperation with civil society organizations and nonprofits working with exiles and political refugees. These actors are essential partners in identifying politically motivated persecution, providing early warnings, and ensuring that responses remain preventative and firmly rooted in human rights protections.

Finding 4: State Collaboration In Forced Removals Highlights Growing Risks For Russian Exiles, Including In The EU

Extraditions and forced removals represent the most dangerous form of transnational repression. These actions pose grave risks to targeted individuals and often bypass legal safeguards designed to protect against politically motivated persecution. While such practices remain most prevalent in Russia’s near abroad, they are increasingly relevant to European security and asylum policies.

In Armenia, for example, at least ten cases of detentions and arrests on Russian charges have been recorded. Although no formal extraditions were confirmed, accounts from affected individuals suggest informal cooperation and attempts to bypass legal procedures. One interviewee described being detained by plainclothes officers and facing an attempt at immediate deportation without trial. Although the attempt failed thanks to legal support, the case illustrates how fragile protections can be in countries with close ties to Russia:

«Six plainclothes men came to me, took me to the police station and tried to deport me to Russia without a trial. I was detained, but thanks to my lawyers I was released after six hours. It was scary because I had a child, and we didn’t know what to do next.»

In Kyrgyzstan, the situation is more severe. Documented cases show direct collaboration with Russian authorities, including the unlawful handover of individuals to FSB agents despite formal extradition requests being denied. Such transfers occurred without legal procedures or official documentation, highlighting the risks posed by states willing to circumvent basic rule of law principles under political pressure. One victim recounted:

«I was placed in a pre-trial detention center for extradition, but the prosecutor’s office refused. However, a month later, officers of the Kyrgyz security service handed me over to Russian FSB agents at the border without official documents.»

While such direct cooperation remains rare within the EU, the underlying risks are growing. Exiled Russians in Europe continue to face significant challenges securing asylum and residency, leaving them vulnerable to extradition requests, deportation procedures, and restrictive visa policies. Notably, cases like the deportation of Alvi Akiev from Poland to Russia in 2024 underscore that politically motivated removals remain a real and escalating danger.

Implications for the EU. Although formal collaboration with Russia is not widespread within Europe, the risks of politically motivated deportations and indirect removals are real and must be addressed. EU member states should adopt comprehensive safeguards to prevent individuals from being returned to face persecution in Russia. This includes clear, harmonized procedures to assess the political nature of extradition requests and deportations, as well as strengthened protection measures for individuals facing indirect or informal pressure to leave. Preventing such removals before they occur is essential to upholding European commitments to human rights and asylum protections.

Finding 5: Transnational Repression Continues to Affect Victims Long-term, Creating Persistent Insecurity

The impact of transnational repression does not end when individuals reach safe countries. For many exiles, including those who have relocated to EU member states, the threat remains very real. Our research shows that TNR continues to shape the daily behavior of victims long after their arrival in Europe. According to survey data, nearly one-third of respondents reported reducing their public and online presence to avoid detection, while others considered relocating again to escape potential exposure. Heightened anxiety and self-imposed restrictions were recurring themes.

First-hand accounts illustrate this reality. One Russian exile living in the EU explained:

«I live in a house with cameras, I try not to trust strangers, especially Russians. I no longer go to rallies, although I used to actively participate. I try not to disclose my location, minimize activity on social networks, and avoid public events.»

This persistent fear is compounded by growing concerns about digital surveillance. Although no direct digital repression cases were recorded in our questionnaire, interviews and reports point to rising risks. Prominent journalists and activists, such as Irina Dolinina, have described how their movements and communications have been monitored, even within the EU. Dolinina received detailed threats while based in Prague and believes her private information may have been accessed through both hacking and official data-sharing channels:

«Digital attacks have been happening for years. […] They found out about our flights, and it’s not necessarily hackers — it could be special services using access to European databases.»

As scholars such as Michaelsen and Thumfart have argued, this digital dimension of TNR presents unique challenges to host state sovereignty. When authoritarian regimes exploit cross-border data access or surveillance loopholes, they undermine the EU’s ability to protect individuals residing within its territory.

Implications for the EU. The persistence of TNR-related fears, particularly in the digital sphere, poses serious challenges to the EU’s asylum and human rights commitments. Protecting exiles requires not only safeguarding them from physical threats, but also addressing covert and indirect forms of repression. EU institutions and member states should strengthen digital privacy protections, enhance oversight of intelligence-sharing with authoritarian regimes, and create targeted support mechanisms for vulnerable groups, including journalists and political activists. Increased training and awareness for law enforcement and asylum authorities are also essential to identify and counter TNR in all its forms.

Methodology and Research Design

Rationale and Approach. While global datasets such as Freedom House’s TNR tracker, the CAPE dataset, the Authoritarian Actions Abroad Database, and the Uyghur-specific dataset offer valuable insights into transnational repression, none provide sustained or comprehensive coverage of Russian-led TNR. This represents a significant blind spot, particularly given Russia’s central role in global repression trends and the growing risks this poses to the European Union. To address this gap, we developed a dedicated research framework tailored to Russian practices. Given the sharp increase in the number of Russian exiles and growing concerns about foreign interference, this approach is particularly relevant to the EU’s evolving security and asylum challenges.

Data Collection and Classification. Our database builds upon the Freedom House methodology but introduces specific adjustments to reflect Russia’s new extraterritorial tactics. Cases are categorized according to host country, year, type of repression, individual profiles, and source verification status. To ensure reliability, each case was cross-referenced using media reports, legal documents, and first-hand testimonies. Consultations with Freedom House experts, notably Yana Gorokhovskaia, further supported the accuracy of classifications.

The sample reflects the migration trajectory of Russian exiles. Many initially sought refuge in Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Serbia before relocating to EU countries. As evidence of repression expanded, the scope of the research was broadened to include additional EU member states with growing Russian diasporas: Bulgaria, Poland, France, Austria, Cyprus, Spain, and Italy.

In response to evolving Russian tactics, we expanded the typology (Annex 1) of transnational repression to include two emerging forms alongside conventional methods such as arrests and extradition attempts. This shift reflects a broader pattern identified by Dukalskis and colleagues (2022), who argue that transnational repression is often an extension of intensified domestic repression. As authoritarian regimes face rising dissent at home, they increasingly seek to neutralize perceived threats abroad. Russia exemplifies this logic, as internal crackdowns have been paralleled by the systematic targeting of exiles overseas.

The first of these emerging tactics, Denial of Entry, refers to politically motivated travel restrictions or border rejections, often aimed at preventing exiles from reaching safe territories. The second, Denial of Services, involves the refusal of essential services such as banking, legal assistance, and document issuance, which undermines the legal security and everyday functionality of individuals in exile. Both have become integral to Russia’s efforts to restrict mobility and exert pressure beyond its borders.

Key Activities (2024). The research combined multiple methods to ensure robust data collection:

- Desktop analysis: Compilation of 118 documented TNR cases since 2014, using open-source data and partner contributions (Annex 6).

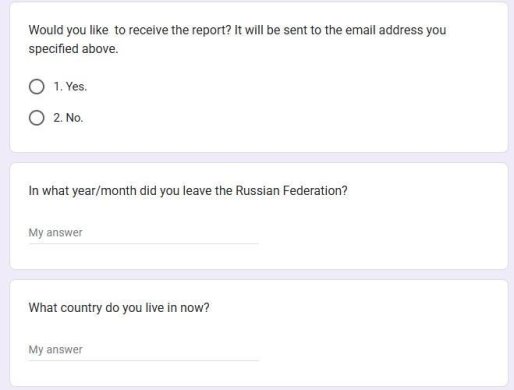

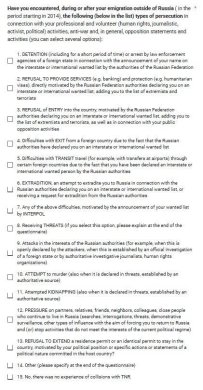

- Online survey: Collection of 40 responses from Russian civil society actors and NGOs in exile to assess prevalence and patterns of TNR.

- In-depth interviews: Conducted with three individuals reporting direct experiences of transnational repression, allowing for case validation and qualitative insights (Annex 5).

This mixed-method approach ensures that the findings presented are based on verified data, offering a rare and reliable insight into Russian TNR practices — and their growing implications for the EU.

Conclusion

Russia’s campaign of transnational repression has evolved into a serious and multifaceted challenge. Initially concentrated in the South Caucasus and Central Asia, TNR has now expanded geographically and methodologically, with new EU member states, including Poland, Italy, Spain, and Romania, increasingly exposed to authoritarian interference. While violent repression persists, Russia’s shift toward covert tactics — notably Denial of Entry and Denial of Services — has rendered this phenomenon more difficult to detect and counter. Furthermore, forced removals and informal cooperation with third states highlight the erosion of legal protections that exile communities rely upon.

Most critically, the persistence of digital repression and intimidation tactics within Europe — combined with widespread anxiety and self-censorship among exiles — demonstrates that TNR does not stop at borders. It challenges European legal systems, weakens asylum procedures, and threatens EU sovereignty by normalizing authoritarian tools within democratic institutions.

Addressing transnational repression is therefore not only a human rights obligation — it is a strategic security necessity. A robust EU-level response must include clear legal definitions, comprehensive data collection, and the formal recognition of emerging TNR tactics. Strengthening partnerships with civil society and improving early-warning and victim support mechanisms are equally vital. Moreover, enhanced oversight of legal and digital infrastructures is needed to prevent the EU’s own systems from becoming instruments of foreign repression.

If left unaddressed, transnational repression risks undermining the Union’s role as a global protector of human rights and safe haven for those fleeing persecution. A coordinated and determined response will be essential to uphold Europe’s democratic values, protect vulnerable individuals, and preserve the sovereignty of its member states.

Annexes

Annex 1. Table: Comparison of Classifications of TNR

Annex 2. Table: Online Questionnaire

Annex 3. Online Questionnaire

Annex 4. Interview Guide

Interviewee Information

Personal Background

- What is your age, education, and current or previous profession?

- What country are you currently in, and how long have you been living there?

- Have you lived in other countries before arriving at your current destination?

- Why did you leave Russia? Was it related to state repression?

- Under what circumstances did you leave the country?

Repression in Russia

- How would you describe your political views?

- Were you involved in any activist or opposition movements in Russia?

- Did you face repression or harassment in Russia? If so:

- What was the nature of the repression or harassment?

- When and where did it occur?

- Were specific articles of the Administrative or Criminal Code invoked?

Repression Abroad

- Have you experienced repression or pressure from Russian authorities since leaving?

- How has this pressure manifested in your current country?

- Does it come from individuals, organizations, or government agencies?

Impact on Life and Safety

- How has your life changed as a result of repression or persecution abroad?

- What steps do you take to ensure your safety?

- Do you receive support from local organizations or human rights advocates?

- Have you encountered challenges when seeking help from local law enforcement?

Future Expectations and Recommendations

- What are your expectations for the future?

- Do you see your future in your current country, in Russia, or elsewhere?

- What safety measures would you like to see for yourself, your family, your colleagues?

- Who should provide these measures, and how should they be implemented?

- What advice would you give to others facing persecution from Russia abroad?

- What actions would you recommend to governments and law enforcement agencies in countries hosting at-risk individuals?

Download PDF version

Download PDF version